Think of a popular film. Star Wars. Superman. Jaws. Rambo. E.T. The Exorcist. Even Some Like It Hot. Whatever you like. Put “Turkish” before it, search it on YouTube, and chances are you’ll witness one of the thousands of cheap Turkish rip-offs that were created in the late 1970s and 1980s.

Turkish cinema has always had a reputation for its “mockbusters”, with cult cinemas around the world regularly screening Dunyayi Kurtaran Adam (The Man Who Saves the World a.k.a. Turkish Star Wars) and Korkusuz (Fearless a.k.a. Turkish Rambo), two films that not only shamelessly rip-off the plots of their American influencers, but also feature actual footage, visual effect shots, and orchestral scores from those films.

Since the dawn of cinema over 100 years ago, every country’s film industry has gone through dramatic changes—but what led Turkey to create so many low-budget curios in the 70s and 80s, until the mid-90s saw the country undergo a creative resurgence?

For that, we must go back in time a couple of decades to the late 1970s, a time of great political upheaval in Turkey… and zero enforcement of international copyright laws.

Artistic Diversity

Politically, Turkey has never been the most stable of countries. Since its creation in 1923, the country has seen multiple coups in the last century, with the military seizing power in 1960, 1971 and 1980 and over-seeing a “post-modern” coup in 1997. Such constant turbulence naturally meant chaotic times for Turkish artists as they had to constantly adapt to ever-changing political tides, facing everything from censorship to violence as the country struggled for democracy.

It wasn’t always this way. Like America, the United Kingdom, and France, Turkey had a golden age of cinema which, like many countries, occurred between the 1950s and 1970s. This “Yesilçam era” got its name from the road in Istanbul that was home to over 40 production companies and much of the country’s film industry

During this time, Turkey was one of the biggest film producers in the Middle East, eclipsing its neighbors in terms of artistic output and winning international accolades for films such as Susuz Yaz (Dry Summer), starring Hülya Koçyiğit, which won the Golden Bear Award at the 14th Berlin International Film Festival.

The secret to the country’s cinematic success was simple. For Turkey’s rural and uneducated masses, cinema was the one thing everyone could enjoy. At its peak, Yesilçam was producing over 300 films a year appeasing every facet of their audience, from young men looking for action films to groups of women looking for romantic escapism.

However, with a limited number of screenwriters, plots were often sourced and ripped wholesale from wherever they could be found. In some instances, the same story would be made three or four times by different distributors just so they’d have something to meet the demand of cinemas around the country. While Turkey had its share of auteurs, Turkish cinema wasn’t primarily interested in awards or any kind of social message – it was about famous actors that the masses wanted to see, a love story and, preferably, at least six fight scenes.

However, political instability and rising costs, due to a failing economy, soon led to Turkish cinema’s decline. The birth of VHS and the creation of Turkey’s television network TRT meant that the country’s filmmakers suddenly had a lot more competition and had to get creative to bring people back into multiplexes.

As such, the last years of the 1970s saw a “sex boom” in Turkish cinema as filmmakers attempted to fill cinema seats with titillation. In fact, 131 of the 193 films produced in 1979 were erotic or pornographic in nature.

The fad was short-lived. In 1980, right-wing nationalist extremists enacted a military coup. Suddenly, political murders gripped the country and going to the cinema, which had once been a communal experience, became dangerous. The country’s film industry changed virtually overnight, as harsh censorship and limitations restricted liberals, artists, and leftists.

Political censorship impacted Turkey’s film-makers massively, especially in the early 1980s when any criticism of the government or the country was either heavily censored or banned outright. The government repeatedly jailed famed Turkish directors like Yılmaz Güney. Many, including Güney, fled the country and eventually died in exile.

Despite their brutal crackdown on filmmakers, the conservative government ironically continued to allow the production of certain soft-core erotic movies throughout the 80s. Apparently, there’s nothing overtly political about some saucy escapades.

Imitation is the Highest Form of Flattery

Since the 1940s, Hollywood has constantly inspired Turkish cinema. However, with numbers of screenwriters at an all-time low in the post-Yesilçam era, it became the main source of new ideas.

Pre-military coup, the only place in Turkey you would see American blockbusters would be the country’s metropolises. For the rest of the country, no one knew about the latest Hollywood movies sweeping the world. Therefore, when the likes of The Wizard of Oz, Wuthering Heights, Superman, and Some Like It Hot were all re-worked to include a Turkish hero and re-shot in a matter of days, audiences were often none the wiser.

As for Hollywood, many studios had no idea that it was standard practice in Turkey to freely cannibalize movies and TV shows. As such, numerous Turkish versions of Tarzan, Flash Gordon, Zorro, and The Lone Ranger thrilled audiences all over the country.

The lack of copyright laws also strengthened the birth of Turkey’s mockbuster industry. Piracy was, and still is, rife within the industry. As such, Turkey’s filmmakers would routinely steal footage, music ,and scripts from other films, add in a few elements of their own and voila! An “original” Turkish mockbuster.

As one director says in the 2014 documentary film Remake, Remix, Rip-Off: About Copy Culture & Turkish Pop Cinema, “I saw a Fistful of Dollars and the next day I remade it!”

Clearly, Turkey’s filmmakers didn’t see what they were doing as criminal. Their love of cinema and a genuine need to feed the country’s love of movies led them to simply take ideas that they saw and “improve” upon them as they saw fit.

Turkish Star Wars

When Star Wars swept the world in 1977, it was inevitable that a Turkish equivalent would soon follow. In 1982, director Çetin Inanç made The Man Who Saves the World, a film that is better known these days as “Turkish Star Wars”.

As Inanç details in Remake, Remix, Rip-Off, when the actual film reels for Star Wars were passing through the country, he simply broke into the studio, cut out the footage he wanted, and returned the reels without anyone noticing. It’s not your average guerrilla film-making technique, but the result is truly something to behold.

Far from being the Star Wars rip-off you’re expecting, The Man Who Saves the World is a crazy mishmash of every popular 1970s and early 80s genre. You have ninjas, spacemen, a monster that looks like it has escaped from Sesame Street, space floozies, and zombies. That’s right. Zombies. In Space.

Sure, the aspect ratio constantly changes. And yes, there is random footage of old NASA launches spliced in. And, for some reason, the score is lifted directly from Raiders of the Lost Ark, but it’s an incredibly entertaining watch as legendary Turkish star Cüneyt Arkin performs a Rocky-esque training montage on an alien world. If that’s not enough, this montage is full of bizarre special effects such as gravity-defying boulders that he constantly kicks while preparing for battle.

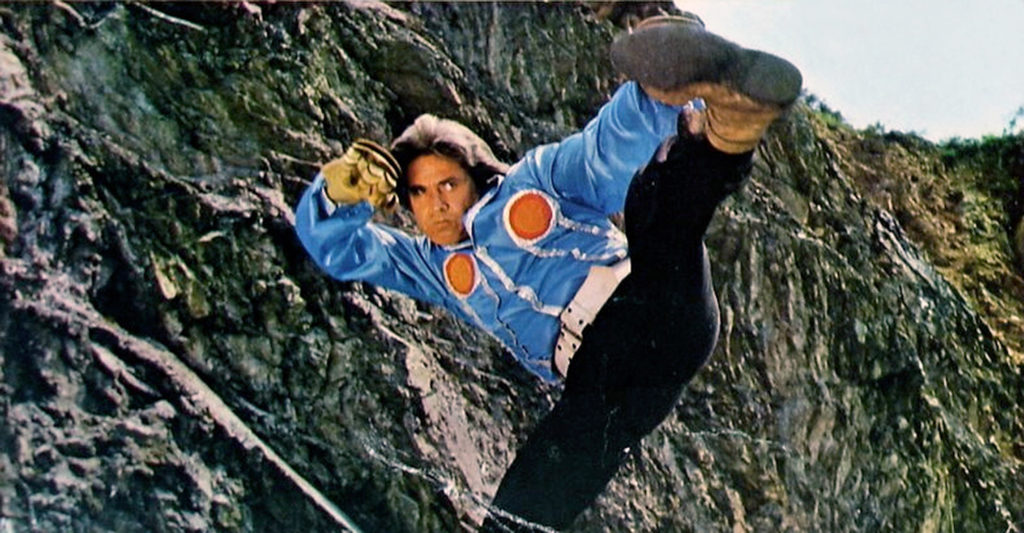

When it comes to the Turkish mockbusters, Cüneyt Arkin is arguably the genre’s most famous actor. With his finely coiffured hair and piercing eyes, the former doctor looked every inch the movie star that he was, and his martial arts prowess perfectly satisfied the country’s desire for action films.

Arkin would go on to appear in over 250 Turkish B-movies where his fighting skills dispatched armies of goons. In interviews, Arkin claims he made so many movies during the 1980s that the film reels could go around the world twice!

The Man Who Saves The World wasn’t the only Turkish film to defy Hollywood’s copyright laws. Decades before the Marvel Cinematic Universe even existed, Turkish superhero film The 3 Giant Men saw Captain America, Spider-man and Mexican wrestler El Santo share the screen for the first time. Of course, in this film Spider-man was the villain and brutally murders a woman by decapitating her with a boat propeller. One can only imagine what Marvel super-producer Kevin Feige thinks of it!

Turkish cinema didn’t just copy American films wholesale; they’d use entire soundtracks as well. If there was a fight scene, directors would use the score from Enter The Dragon. A tragedy? The Godfather waltz became the music of choice.

This unique clash of elements and mixing of genres led to pretty unique and, at times, bewildering films. However, the government seemed to generally turn a blind eye to these low-budget curios. As such, some of the country’s most distinguished filmmakers—such as Memduh Ün, who received international recognition for his film The Broken Pots—ended up making low-budget movies like Cellat (“Turkish Death Wish”) to continue working in an industry where political and socially conscious movies were banned.

End of an Era

Çetin Inanç went on to offer takes on more American blockbusters like Jaws and Rambo, butThe Man Who Saves The World is still regarded as his most famous film. Despite an unfair reputation as Turkey’s Ed Wood, Inanç has embraced his film’s legacy and regularly attends sold-out screenings all around the world.

Starting in the mid-1990s, Turkish mockbusters began losing steam. Cinemas began attracting audiences again, and several Turkish films won critical acclaim at international film festivals. There was just no demand for lo-fi, no-budget films anymore when people could afford to go to the cinema and see prestigious work with real production values. As living standards increased, it seemed as though audiences’ expectations of quality increased, too. Mockbusters would become relegated to the fringes of cult cinema as Turkish audiences gained other options for entertainment.

However, while the revival of Turkish cinema pleases critics and cinephiles alike, cult film fans are content with the hundreds of films produced during the country’s lowest point. Sure, Turkey’s new wave of films embrace its ideals of identity and national pride, but do they feature scenes where Turkish Batman battles a villain that looks suspiciously like James Bond’s nemesis Blofeld? Alas, they do not.

However, Turkey’s democratic freedoms may yet again be in jeopardy. Over the past decade, Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has cracked down on protests, jailed journalists, and curtailed individual freedoms. Now, with 2018 seeing Erdoğan becoming both Turkey’s head of state and head of government and tightening his grip on power, what’s to say that the country’s filmmakers won’t again push back against increasing restrictions? Perhaps, another resurgence of Turkish mockbusters might be on the horizon.

Timon Singh runs The Bristol Bad Film Club in the UK, which screens cult movies every month to raise money for local charities. August’s screening is of Who Killed Captain Alex?, which CE has called “The Most Important African Film of the 21st Century”. Timon’s first book, Born To Be Bad: Talking to the Greatest Movie Villains in Action Cinema, is out later this summer from BearManor Media.