As we’ve explored in previous reviews, North Korea actually makes a fair number of movies — from the Godzilla ripoff Pulgasari to the revolutionary opera-based The Flower Girl. That’s helped in part by the fact that Kim Jong-il is a massive film buff, with one of the largest private movie collections in the world. Nevertheless, the world of North Korean film remains largely unknown to Western audiences…until now.

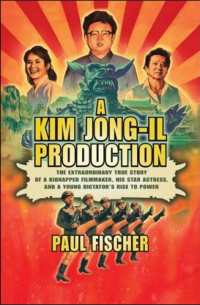

Today we present a special interview with Paul Fischer, whose recently released book A Kim Jong-il Production: The Extraordinary True Story of a Kidnapped Filmmaker, His Star Actress, and a Young Dictator’s Rise to Power peels back the curtain on North Korea’s cinema spectacle.

Fischer’s book documents the story of South Korean director Shin Sang-ok and his actress wife Choi Eun-hee, who were kidnapped and brought to North Korea by Kim Jong-il in the late 1970s.

For almost a decade, the couple remained there, surviving stints of isolation and imprisonment before being forced to help Kim cultivate the regime’s domestic film industry. Through the lens of Shin and Choi’s experiences, Fischer explores the role and development of film in North Korea, a country that can itself feel like a massive movie set.

Last week, Fischer answered some questions I posed to him about his book and North Korea at large — read our conversation below.

Your background has primarily been in film — you produced a documentary about a homeless man who had perennial cameos in Hollywood movies, and you studied film at USC and the New York Film Academy. What first sparked your interest in North Korea, which, at least to the casual observer, seems quite far away from the worlds of Steven Spielberg or Francois Truffaut?

It was this story [of Shin and Choi] itself, which I’d read about in newspapers here and there — the story of a down-and-out filmmaker “offered” the opportunity to revive his career, with unlimited resources, but it means serving a dictator and making films supporting him. I was always fascinated by that Faustian pact.

Originally the basic concept was something I wanted to turn into a work of fiction — something, I guess in hindsight, a bit like Cecil B. Demented — and it’s only when I looked into the details themselves that I knew this had to be non-fiction, and that it revealed something about North Korea.

There’s a common perception that North Korea is an immensely inscrutable topic, and the story of Shin Sang-ok and Choi Eun-hee isn’t necessarily straightforward either. How did you go about researching the country and the couple, and what aspects of that process were particularly challenging?

I actually sort of disagree with that notion. It’s hard to understand what, politically, say, Kim Jong-Un might do day to day or why, and there are big gaps in understanding of the culture; but at the same time there’s been so much fantastic scholarship, research, documentation, and journalism on the country in the last several years that we kind of understand it more than we act like.

There’s an Internet joke among North Korea writers and watchers about the “rare glimpse” syndrome — which I’m sure this book and its marketing will be guilty of here and there: that everything about North Korea bills itself as a “rare glimpse” into the state, but if there’s a thousand rare glimpses, how rare are they?

Before I started writing the book, I didn’t understand North Korea and how it worked. I assumed no one did, because that’s the impression the mainstream media gives. But it turns out, just beyond lazy mainstream media, there’s actually a lot of information out there that makes it much more comprehensible.

As for the story itself, it was a lot of fact-checking, of being thorough, of being rigorous and open-minded. I looked into everything I could — read everything, watched everything, spoke to everyone. That started making sense of things and I could connect dots that people hadn’t seen before perhaps.

You’ve mentioned in other articles that you visited North Korea during the course of writing A Kim Jong-il Production— how did the fact that a) you’re a filmmaker and b) you were researching this book shape your perception of the tour? Did you specifically request to visit any film-related sites such as the Pyongyang Film Studio?

I did, and they catered to that slightly in my schedule but I think many tourists see the studio — it’s a standard tourist stop. I told them I was a filmmaker, off the bat, so it would make sense when we talked about film stuff or if I had intrusive film-related questions. That I was writing the book meant I was very interested in all the ways they micro-manage your time and try to deceive you — the guides, the lies, the acting like everything is friendly and impressive — instead of feeling just purely tricked and bored by them, as a regular tourist might.

When I toured North Korea last summer, one of my guides told me how he’d seen Titanic, Toy Story, and even The Patriot (at least as part of his elite English-language instruction). While in the country, did you manage to talk personally with any North Koreans about cinema, or perhaps even gauge what their ostensibly “official” perception of Shin-directed films like Hong Kil-dong or Pulgasari were?

Did you test him on that? It’s one of the things that’s weird — many guides have genuine knowledge of odd foreign things (one of my guides was very into the idea of WikiLeaks), but equally often they’re briefed to say things they don’t fully understand. So he might have been given these titles but never seen them, and if you’d asked him about it, say, he might not have been able to say what any of those movies are or what happens in them. A recent BBC documentary showed a North Korean student who said he’d studied in the UK for years, but when quizzed he knew nothing about the country and it was clearly bullshit he’d been told to just say to be impressive.

I kept asking about Shin, especially because my older guide was the right age to have seen and remembered his films. But of course after he and Choi left, there was a big propaganda drive to erase them from history, so she acted as if the name rang no bells — when clearly it did. Hong Kil-dong is on sale on DVD there to foreigners, but his name is no longer on it in any way. Interviewing defectors was much more helpful in getting an idea of film-going in North Korea, because they’re of course able to speak more freely.

I recently read this article you wrote for The Guardian, in which you compare North Korea to The Truman Show. While the perception of North Korea as a “theater state” appears pretty substantiated, do you think there might be some danger in characterizing the country that way? Do we perhaps risk dehumanizing regular North Koreans if we implicitly treat them as actors — who don’t necessarily have individual agency — on a monolithic movie set?

I don’t think so, no, because it’s the state we’re talking of, the framework — not the people. In The Truman Show, Truman is very human, individual, relatable, and that’s key to why the analogy strikes a chord for me. The whole point of the article is the idea that the state tries to take that away from the people, tries to make them seem homogenous and faceless — tries to make them act homogenous and faceless.

The words that fit the state framework aren’t the same that fit the people, usually. An African state can be violent and corrupt without it being a reflection of the people or culture. In the US and the UK, we live in Big Brother states for which freedom takes a back seat to “security” and paranoia — but obviously that’s not the mindset of the majority of people, who aren’t dehumanized “targets”. North Korea’s the same. The fact that the Kims have built a set and written a script doesn’t mean the people coerced into it are fake.

If North Korea is a “theater state”, then who do you think is its audience? Its people? Us in the outside world? Both? If we non-North Koreans are an audience, could we sometimes become unknowingly complicit in the regime’s machinations?

Both, separately, and you can see that because the propaganda fed to the domestic people is different from the propaganda fed us. And we’re definitely complicit in a tacit way. The regime still stands in part because the West, South Korea, China, Japan don’t want to deal with the uncertainty of the alternative.

And our own narratives — that we still use the Cold War, communist, etc. lingo, when it doesn’t apply — plays into the regime’s hands too. That we play the footage of the mass games on the news, play the footage of the big state funerals with people desperately trying to appear hysterically sad…all that keeps North Korea in this otherworldly realm which is where the Kims are happy for it to be.

In your book you write how, as mediums for North Koreans to peek at a world beyond their own, “Shin and Choi’s movies were drops of water, each one slowly but surely wearing away the Kims’ supremacy”. In the past few years, there’s been a limited degree of foreign film collaboration with North Korea — for instance Comrade Kim Goes Flying (co-produced with the UK and Belgium) and Meet in Pyongyang (co-produced with China), both from 2012. Do you think these recent efforts are also “drops of water” wearing away at the Kim regime, or just attempts by that regime to build international legitimacy and bring in foreign capital?

A bit of both — kind of like Shin and Choi’s films, really. The co-productions are approved and vetted by the Kim regime, they’re shop windows for the regime, they make current North Korean culture — which is one of fear and oppression — look benign and cozy.

In those ways they’re dangerous. But they also humanize North Korea to Western audiences who may otherwise only see North Korean people on the news, as part of these big machinations and nuclear tests and mass games and all this stuff, and forget that they’re human beings with the same emotions as you and me. And surely the more we relate with the people being oppressed in North Korea, the worse it is for the regime, because we start caring what happens to them. But that’s a very slow process, and not best achieved necessarily by films that are censored and cut out big swatches of the truth, and I don’t think Comrade Kim Goes Flying is turning anyone into anti-Kim activists.

The documentary co-productions – A State of Mind and The Game of their Lives and so on — are more helpful, because it’s real people, so real stuff seeps through.

Just to wrap things up on a lighter note — if you had to recommend one North Korean film to Cinema Escapist’s readers, which one would it be and why?

The Flower Girl is kind of a seminal, representative film. And Pulgasari is fun as hell.