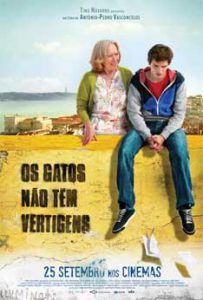

Thanks to Stanford Global Studies’ Summer 2016 Film Festival, I recently had the chance to see the Portuguese film Cats Don’t Have Vertigo (Os Gatos Não Têm Vertigens), followed by an insightful Q&A with Vincent Barletta, an Associate Professor of Comparative Literature and Iberian and Latin American Cultures at Stanford University.

Despite having little English-language media coverage (not even a Wikipedia article), Cats Don’t Have Vertigo is a surprising gem with a heartwarming, universally accessible story. Set in the picturesque Alfama district of Lisbon, the film documents an unlikely friendship that develops between a 73-year old woman named Rosa and an 18-year old boy named Job (Jo in Portuguese), touching upon a broad range of social and political issues relevant to contemporary Portugal in the process. You could say the movie’s like a Portuguese Harold and Maude.

Recently widowed, Rosa struggles to move on and find new meaning in life. When she finally ventures out of her stately apartment, a group of boys steals her purse. It just so happens that one of those thieving boys is Job. Abandoned by his mother and abused by an alcoholic father, Job runs away from home after a fight and finds himself living on the roof of Rosa’s apartment after fishing her keys from the stolen purse.

It’s as if a stray cat (thus the title) has stumbled into Rosa’s life just as she most needs the strong-willed companionship that only a (metaphorical) feline can provide. The relationship starts discreetly: she surreptitiously feeds him, he slinks away and then back again (an aside: listen for the soft “meow” audio motif whenever Job comes and goes as an extension of the feline metaphor). Eventually, they confront each other — and though Job might’ve helped steal her purse, the strong-willed, good-humored Rosa doesn’t care. She knows that this stray cat is going to keep coming back to its new home.

Economic crisis

A latent yet significant undercurrent within the film is Portugal’s contemporary economic situation. When Cats Don’t Have Vertigo was filmed in late 2013/early 2014, Portugal had already undergone several years of economic recession as part of the broader European sovereign debt crisis. Unemployment was high, the country’s bonds had junk status, and the government had implemented an unpopular austerity regime in order to receive a IMF/ECB-led bailout.

The first way Portugal’s economic woes appear is through the hopelessness that Job and his other young friends exhibit. Job’s dad is heavily in debt, his best friend’s mom can only make money as a prostitute, and all of them spend their time committing petty crimes and not in either employment or education. Near the end of the film when Job is hanging out with his best friend, they make a bitter pronouncement in regards to Portugal’s situation: “too many whores, and not enough clients.”

Beyond that, especially after her purse is stolen, Rosa’s son-in-law is especially insistent on selling off her apartment and sending her to a retirement home. “There’s someone interested in your place, which is completely unheard of these days,” he insists, accurately. Though the situation is improving somewhat, back in 2013/14 Portugal’s real estate market was still absolute garbage — there were (and are) supposedly entire apartment blocks in Lisbon that have been abandoned and boarded up for lack of buyers. Even when Rosa walks around to shop there’s signs of economic distress: her regular butcher has gone out of business, and her greengrocer suspects she may be next.

Probably the most direct reference to the Portuguese recession, though, is a somewhat tangential scene during which Rosa bumps into her neighbor, a man in his late 20s or early 30s, and invites him in for lunch. Over homecooked food, he tells her how he lost his job as a designer, can no longer afford to pay for his apartment, and will be moving back to live with his parents in the countryside. “Maybe I’ll milk cows and help out on the farm for a change; nobody needs designers anymore,” he sighs in resignation.

Legacy of the 1974 “Carnation Revolution”

From 1933 to the 1974, Portugal was ruled by an authoritarian dictatorship known as the Estado Novo. In part due to growing discontent over expensive wars the government was fighting to retain Portugal’s overseas colonies, the country erupted into what became known as the Carnation Revolution on 25 April 1974. The dictatorship fell, the wars ended with colonies gaining independence, and there was a general sense of optimism and possibility as a democratic Portugal emerged.

In Cats Don’t Have Vertigo we learn that Rosa and her late husband Joaquim were dissidents against the Estado Novo who underwent great personal pain and privation to help bring about today’s democratic Portugal. However, given the economic context, that Portugal of today isn’t exactly the most wonderful place in the world. Furthermore, the young Job has no idea that Portugal used to be a dictatorship and little knowledge of anything except the miserable present, making it seem like the sacrifices of Rosa’s generation were for naught.

Today, this feeling of disillusionment overshadows Portuguese society. In fact, in response to the financial crisis, one of the leaders of the Carnation Revolution was actually quoted as saying “if I knew how the country was going to be, I wouldn’t have made the revolution.”

Generational divides

Gulfs between different generations are not exclusive to Portugal; this is one reason why I think Cats Have No Vertigo is a highly relateable film that should’ve enjoyed more international attention. At the same time, Portugal’s economic crisis has distinctively exacerbated generational issues and disrupted traditional notions of family life and community structure.

Life for the old and young are both challenging in Portugal, though in different yet interrelated ways. When adult children like Rosa’s neighbor go back to live with their aging parents, those parents must provide for yet another individual amidst declining pensions (something Rosa notes during the movie) and a shabbier social safety net (thanks to austerity). Furthermore, many of the best-educated young Portuguese have chosen to emigrate abroad in search of better opportunities. This leads to many grandparents living by themselves, feeling increasingly alienated because their children live in a foreign country and their grandchildren are unable to speak Portuguese. For young and old alike, the future appears bleak (though admittedly some improvements are occurring).

Overall, despite its limited popularity, Cats Don’t Have Vertigo provides a surprisingly incisive snapshot at Portugal’s contemporary social situation. From artistic and entertainment perspectives it’s quite decent too with a heartwarming yet bittersweet tone, creative plot elements, and beautiful shots of the Lisbon cityscape. In a darkly poetic way, the film’s relative lack of publicity may be a result of the very situation it sheds light on. With a small domestic market (Cats Don’t Have Vertigo made around €500,000; considered pretty good for a local film; Portugal’s population is only 10.46 million) and limited funding sources (think of how many people in Portugal would invest in a film after all the big banks have collapsed, and think of how many foreigners want to invest money in a small Portuguese film), this cat could unfortunately only trot so far. If you do get the chance to see it though, seize it.

Cats Have No Vertigo (Os Gatos Não Têm Vertigens) — Dialog in Portuguese. Directed by António-Pedro Vasconcelos. First released September 2014. Running time 2hr 4min. Starring Maria do Céu Guerra, João Jesus, Fernanda Serrano, and Ricardo Carriço.