This author has consistently argued, to much ridicule, that a movie which proudly declares that everybody in Uganda knows Kung Fu can be compared to masterpieces like Ousmane Sembene’s Black Girl, Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, and Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight. But you would be surprised how much these four films have in common, even though one of them features a helicopter literally flattening a skyscraper whilst a narrator screams “What Is Happening?!?! Hello!” at the top of his voice.

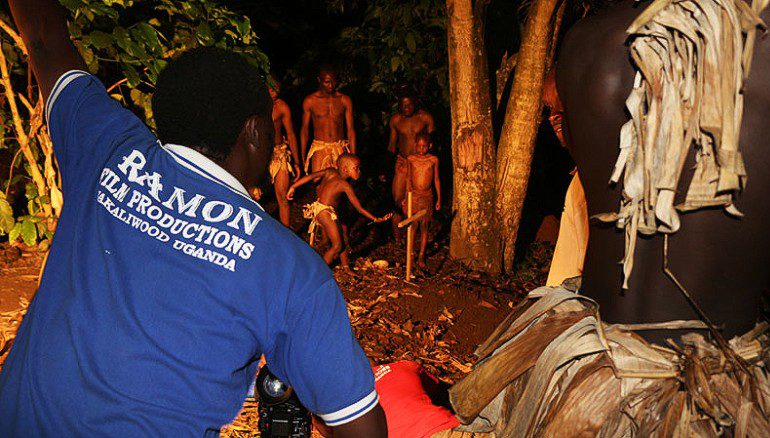

Director Isaac Nabwana’s Who Killed Captain Alex?, the absolutely ridiculous “Supa Action” movie from the slum of Wakaliga near Uganda’s capital, Kampala, became a viral hit when its trailer was uploaded to YouTube, amassing millions of views across the globe.

What Nabwana has achieved in Wakaliga since then is nothing short of remarkable. He has almost single-handedly created an industry. He inadvertently capitalized on the crossover appeal of genre films, and through his love of vintage Martial Arts movies has developed the kind of relationship with the Chinese market that no other African filmmaker has done.

Nabwana’s maverick approach is markedly different to other film industries within Africa, leading him to the kind of success they have been unable to achieve. All this from the creative mind behind Ebola Hunter and Cannibal Mama.

To date, Who Killed Captain Alex? is the magnum opus of both Nabwana and Wakaliwood and it is the most important African film of this century so far. It indicates a way forward for African Cinema to become a more vocal force on the world stage, and looking at the making of this ludicrously entertaining film is a great way to chart the evolution of African Cinema in the last 55 years, which draws certain parallels to the birth of Western Cinema.

Milestone films that are announcements

Black Girl. Killer of Sheep. Moonlight. Three films, two from African American filmmakers, that stand out not just because of their quality, but because they are films that broke new ground. The first truly African film by an African filmmaker. The first film to come out of the L.A. Rebellion school of filmmaking, by one of the first publicly recognized African-American filmmakers since Oscar Micheaux. And a bold coming-of-age gay love story depicting a truly African-American experience that successfully crossed over into the mainstream and awards glory.

The common thread between these films is that they were announcements of a new type of filmmaker, or a new type of storytelling, or both. They spearhead what I consider to be the three phases of African and African-American Cinema (more on that in a moment). Just the fact they exist is enough of a milestone. The fact they are masterpieces has ensured they are more than just an interesting historical marker. (There are, of course, other notable landmark films in African and African-American Cinema, such as Cheryl Dunye’s Watermelon Woman, but the three aforementioned examples have penetrated the public consciousness to a far greater extent)

So what does Who Killed Captain Alex?, a film whose narrator blurts out “dinosaurs” with no context as its hero hides among a flock of Pelicans, have to do with these masterpieces? It achieves exactly the same thing, announcing a new type of filmmaking to the world, although by accident- Nabwana only made his film for the entertainment of the people of Wakaliga, but when it got uploaded to YouTube it introduced the internet to a unique piece of African filmmaking. The film has achieved the same sort of impact as the aforementioned films, on a larger and less intellectual scale.

Black Girl is an essential part of a continent-wide sweep of political development, but Who Killed Captain Alex? is solely made to entertain. This does not dilute its contribution to African Cinema, in fact quite the opposite- like Black Girl, it is a film that spearheads a phase of African Cinema.

Three Phases of African Cinema

I believe that, for the sake of simplicity within this article, African Cinema’s history can be broken down into three broad phases. Briefly, my definition of the three phases of African Cinema- which I believe also roughly applies to African-American Cinema as their developmental stages, in the broadest possible sense, run almost in parallel- is as follows:

Phase One: Distinctly Independent Cinema (1963-1993 approx.)

African Cinema (or what could also be referred to as Post-Colonial African Cinema, but I believe this terminology to be inaccurate) was born in 1963 with the release of Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembene’s short film Borom Sarret (The Wagoner), and truly arrived with his debut feature film La Noire De… (Black Girl) in 1965.

Africa was becoming increasingly independent, in terms of sovereignty at least, during the time of these films. Pan-Africanism was becoming far more prominent, and Africans were in some ways beginning to shed the gentrified culture enforced upon them by oppressive colonialism. Sembene was a pioneer in truly reclaiming African culture and telling African stories, both in literature and on screen.

However, with Colonial forces leaving, there was clearly little desire for them to share and exhibit African films in any great way- it would have been a further demonstration of their perceived failure to maintain control. The West was making enough money- and influencing their own culture with movements like French New Wave, Italian Neorealism and the “Movie Brats” of Hollywood- that they had no need to show audiences what Africa was producing.

This is where the biggest issue that still limits the potential of African Cinema originated- seriously underdeveloped models of exhibition and distribution. As Africa rebuilt in the post-colonial era, Cinema was considered as hardly an essential factor in the development of an independent continent, compared to infrastructure and economic sustainability. Certain African countries nationalized their cinemas to ensure the production of empowering, indigenous films, but upon first glance it appears that far more should have been invested into these national Cinemas.

African Cinema, as advanced as it was becoming, was not truly independent from forms of European influence. Sembene still relied on French support to get many of his earlier works made- he educated himself and developed his artistic occupations whilst in Europe, which he then brought back to the continent.

African Cinema was also hindered by a lack of technology and education in filmmaking, as well as a lack of development in the business side of the film industry- it would hardly benefit the West to support the continent in these regards, as it would be a way to increase Africa’s “soft power” and cultural impact across the world, especially within the Soviet Union.

There were many incredible African films made during this period, but even today many of them are hard to find. There are a variety of reasons for this, such as a lack of proper preservation of original negative prints, a lack of awareness among African audiences, and a lack of voices bringing African Cinema into mainstream conversation. Because these films weren’t exposed to a significant audience or upcoming filmmakers during the first three decades of Phase One, it’s no surprise that they don’t come up in conversation with anyone but the most cineliterate or dedicated enthusiasts.

A lack of desire from international markets to support African Film in a significant way, combined with a lack of resources and technology to preserve and develop, plagued this difficult first phase which produced some remarkable films and filmmakers, who remain criminally under-exposed.

Phase Two: Bold Introspection (1993-2010)

“There are so many flashbacks in African films, it’s as though the continent is always remembering.”

—Mark Cousins

Haile Gerima’s Sankofa and Roger Gnoan M’Bala’s Adanggaman are, to my mind, two of the best films from my self-defined second phase of African Cinema. Once again, I say this in the broadest sense, but they draw comparison to certain African American films such as Julie Dash’s extraordinary 1992 film Daughters of the Dust. These three films represent attempts to address the past, namely the occupation of rediscovering a pre-colonial history in relation to the impact of the slavery and colonization.

There was less of a sociopolitical motivation to leave an African mark on the cinematic medium, as this had been achieved over the last three decades. Instead, we began to see more stories that reflect on deeper questions like African identity, and an independent Africa’s place in the world.

Sankofa‘s director, Haile Gerima, is an African filmmaker who was part of the L.A. Rebellion movement in the USA, and his film deals with the Diaspora’s need to remember its heritage. Adanggaman is a scathing examination of Africans’ role in the Atlantic Slave Trade. These kinds of films feel less immediate and more philosophical. This represents a much-needed evolution in what sort of African stories were being told. Many films from this phase feel more like poetic contemplations than aggressive critiques. Directors like Abderrahmane Sissako, as well, represent an increasingly emotionally complex, philosophically sophisticated and sensitive type of African Cinema.

The limitations of Phase One remained. As the West experienced the benefits of the digital revolution, and film production became more democratized, in Africa there was still a lack of preservation, education and development on any great scale across the continent. Whilst progress was slow, the Diaspora’s Cinema, especially in America, was thriving around this phase with filmmakers like Spike Lee and Tyler Perry offering vastly different films. Sembene’s work slowly found some sort of second life in Europe, but that was confined to academia and the cinephiles.

Beyond the festival route, African Cinema still didn’t penetrate the mainstream in any way since the derivative and diminishing The Gods Must Be Crazy franchise a decade earlier (it should be noted they found success in Asia, but more on that later).

Progress was being made, of course, but it’s hard to identify any notable cinematic movement or evolution of Africa’s film industries in a business sense. At least, not without referring to relations with the West. To refer to this second phase as “The Wilderness Years” would be a gross exaggeration, but artistic breakthroughs were not translating to the development of the continent’s cinematic culture or its global influence.

Phase Three: Overcoming The Past (2010-Present)

This is where Who Killed Captain Alex? comes into play. It marks a totally different kind of African film- one that is not about reflection, introspection or announcement. It is an attempt at commercial, mainstream entertainment. The fact it is a piece of Genre cinema is crucial, too. There is nothing academic, analytical or intellectual about it- the film’s only intention is to be a film. It exists in an absurd reality slightly removed from our own. That alone demonstrates a shift in the kind of stories being told in Africa, by Africans.

There is no other film quite like Who Killed Captain Alex?, and despite the obvious influences of Western action films and Chinese Martial Arts films, it does not strictly adhere to their traditional structures. It cannot just be written off as an attempt to enter into those canons of filmmaking.

The likes of Sissako have led the way in presenting bold African filmmaking in the last decade, but these films and filmmakers are still not getting out there to wider audiences, unless those audiences really put in effort to seek them out.

Who Killed Captain Alex? doesn’t have this problem. It was a film that was presented and marketed in a different way to other African films, and enjoyed worldwide attention because it was not so culturally specific as to be restrictive to wide audiences.

It’s hard to really map out this phase as I consider it to be ongoing. But when Who Killed Captain Alex? arrived, there was no going back. It demonstrates that the issues plaguing the exhibition and distribution of African Cinema’s rich variety of stories can be overcome. But there is still a way to go.

Now we have a brief overview of African Cinema’s history, just what makes Who Killed Captain Alex? the most important African film that has been offered up in the last 18 years?

Comparing Wakaliwood to the Silent Greats

“Nabwana is the first true African movie mogul.”

It’s easy to compare what Wakaliwood is doing to what the early pioneers of Hollywood did. Chaplin, Keaton and the studio moguls were a bunch of entertainers messing around in the California sunshine, in self-imposed exile to escape the monopolistic clutches of Thomas Edison over on America’s east coast. Their experimentation led to the most powerful global cultural institution of the last 100 years. One look at Wakaliwood’s growth, and its continued international attention through various press outlets and film festivals, draws very promising comparisons- but on Wakaliwood’s terms. It is not imitating Hollywood, but shows the same potential.

It cannot be argued that Africa Cinema is in its infancy, especially as it is a continent which contains the world’s third largest film industry, Nollywood. But Who Killed Captain Alex? was not part of a nationalized cinema, and it breaks new ground on multiple levels in the same way that Hollywood’s film industry did back when it started. It all starts with Nabwana- he has more ambition for Cinema beyond the art of filmmaking than perhaps any other African filmmaker in history.

“I know we need good cameras, computers but even without, you can not just sit, we have the talent, we have the passion, we can do it… We are training children, they are ten in number. They are going to be the future of this industry. If you are to build a film industry, we have to start from children… My dream is seeing a big studio with the young generation learning how to edit, direct and write scripts. That is my dream.”

—Isaac Nabwana

Comparison to the silent era of Hollywood reminds us that Nabwana is the first true African movie mogul. Like all moguls, he has thrived by making use of developing technologies. Unlike the pioneers of Hollywood, both Nollywood and Wakaliwood have an extraordinary tool at their disposal- but only the latter has made use of it to attract the wider world. The likes of Nollywood seem content where they are, and that is a big problem. They see no need to reach out beyond their receptive audience, and in the face of Globalism that is a poor move.

Utilizing The Internet

The internet allows for overcoming the historical problems of distribution that have crippled African Cinema. There are not enough movie theaters, or digital platforms that are accessible to African audiences. Of those that exist, African films are not as popular as international fare so are not as commonly exhibited. There is a lack of outlets to educate Africans of their cinematic history, and that is partially because so many classic African films have not been preserved and restored. This lack of infrastructure makes it even harder to alter the situation. These problems have plagued African Cinema since the middle of the 20th Century, and until recently we have seen little effort to resolve the matter.

The trailer for Who Killed Captain Alex? arrived on YouTube to little fanfare, until it quickly exploded into the most-exposed piece of African filmmaking ever. Wakaliwood’s work has received tens of millions of views on the internet, and all despite a budget of approximately $200. The Internet truly democratizes filmmaking, and Who Killed Captain Alex? is the first African film that has taken advantage of that.

The film’s random, madcap humour has tapped into meme culture, another reason for its longevity. Virality was clearly not Nabwana’s intention, but his creation has amassed a cult following who have sustained the film’s popularity on social media. It’s unlikely Who Killed Captain Alex? will achieve the recent crossover success of Tommy Wiseau’s The Room, but the financial support of its fanbase allows for Wakaliwood to be a full-time profession for Nabwana and many of the people of Wakaliga. No other African film can boast this kind of influence or success.

Who Killed Captain Alex? became a viral hit for several reasons, one of which is the kind of film it is- a piece of Genre filmmaking.

Genre has crossover appeal

“I don’t see a more effective way to increase Africa’s presence… than producing more Genre films.”

This is a point I have brought up before many times, because I believe this is the best way to kickstart a fourth phase of African Cinema. As covered in my article about the doors that Black Panther has potentially opened to audiences, to expose them to more authentic African storytelling, high-concept genre filmmaking transcends cultural boundaries. There is a reason that superhero films and action-heavy blockbusters like the Fast and Furious franchise have performed so well internationally. Who Killed Captain Alex? provided action filmmaking on Ugandan terms. It may have been creatively influenced by both East and West, but the viewer is always aware that it is a Ugandan film.

Something many African Cinemas seem to struggle to understand is that the vast majority of cinemagoers are not interested in high art that might perform well on the festival circuit. But Nabwana understands this. Most moviegoers don’t always want profound, challenging films- sometimes they just want to have a good time. Cinema started as a form of entertainment before it became primarily about business. Action, Horror and Sci-Fi films trade in the emotional manipulation of the audience. You don’t need to read subtitles to appreciate stunt work or an effective scare. These are the tactics of Silent Cinema, as previously mentioned. This kind of kinetic cinema will reach wider audiences and be a much easier sell to distributors both niche and mainstream.

I don’t see a more effective way to increase Africa’s presence in the global cinematic conversation, advance the growth of its moviegoing culture and become a more financially influential market, than producing more Genre films. As far as I’m concerned, this is the best way to overcome traditional hesitance to African fare- until distribution and exhibition models improve within Africa, then it is offering far more universal entertainment that will attract the world to what African Cinema has to offer.

As one of the few filmmakers to be part of this solution to the issues that have held back African Cinema, Nabwana has taken this a step further- the inspiration for Who Killed Captain Alex? has brought him into the orbit of the most important film market of the present day.

Nabwana’s relationship with China and Martial Arts

“We love the Chinese culture of Kung Fu which has its own importance like body fitness, self-defense … we need that in our society, it is almost a medicine,”

—Isaac Nabwana

Through a long-time passion for martial arts movie from the East, Nabwana seems to be one of the only African filmmakers capitalizing on Chinese interest in the continent. A recent documentary saw Nabwana visit China, as part of the latest Wakaliwood epic Bruce U was shot in the South Shaolin Temple, and features Chinese actors.

As it becomes the largest film market in the world, Western filmmakers are scrambling for Chinese money with very mixed results – The Great Wall, Iron Man 3 and Transformers being notable culprits of trying to appease Chinese audiences who were left unimpressed- and the key seems to be not pandering to them. Nabwana, however, has a deep personal connection to this particular market and it kickstarted his journey as a filmmaker. It is this sincerity that will attract international audiences in the long-term.

Overlooking the potentially more sinister and disturbing complexities of Sino-African relations, as economic and political oppression in a different guise, there are shared interests for African nations and China, especially in undermining America’s soft power. It only makes sense these shared interests would include the arts as well. Through Wakaliwood, Uganda is at the forefront of business and cultural relationships with China and its resources. If China pushes for as much development and intersection in Cinema as they have in so many other parts of the Continent, it will accelerate awareness of African Cinema- and Nabwana’s films would have started it all.

“Bruce Lee was famous here, and I think he is one of the few Chinese who sold the Chinese image in Uganda… [he] made a very remarkable impact on us,”

—Isaac Nabwana

Crucially, Who Killed Captain Alex? is an African film primarily influenced by Eastern culture. This is another reason it is such an important film. It cannot be categorized as a parody of a certain country’s Cinema- it is a truly international film. Nabwana has developed an international outlook far earlier than any of the Hollywood studio moguls ever did. As Wakaliwood becomes ever bigger, their outward look is what will usher in the fourth phase of African Cinema- one that the world will be watching.

Justifying the film’s importance

“…films like Who Killed Captain Alex? will give the entire heritage of African Cinema back to Africans”

It can certainly be problematic to assume Who Killed Captain Alex? is important just because it is seen by a wide global audience; that African films that haven’t been so popular aren’t as important for the artistic techniques they employ, or the issues they address, or ground they break within their own country.

This thinkpiece could be criticised for being yet another analysis written within a Western frame of reference- that I am praising Who Killed Captain Alex? because it adheres to my Western perceptions of what cinema is and how stories should be structured. And there may well be an unintentional, subconscious element of that, especially in my earlier comparison of Nabwana’s efforts to that of the early Hollywood moguls.

I am not saying Who Killed Captain Alex? is the best African film of this century, but it is the film that signifies a shift in cultural influences, of overcoming the continent’s past limitations in distribution and exhibition, and responding to a supposedly decolonized, increasingly globalized world, where power is shifting Eastward. It has actively changed a certain part of African Cinema, and crucially exposed a wide variety of people outside the continent to what is being produced in Uganda.

Doubtlessly to the chagrin of far more seasoned experts and academics in the field of Africa Cinema, I have always used the term “African Cinema” to refer to the cinematic output of the Continent’s 54 countries, unless referring to a very specific National Cinema, such as Nollywood, in the context of an article. But I believe this umbrella term is appropriate, and arguably more appropriate than breaking down the continent’s Cinema into its linguistic regions.

How can conversation turn to National Cinemas when the vast majority lack an awareness of the vast distinctions between African nations and their cultures? Before the conversation can advance, it needs to really get started. General audiences do not inherently refer to the Cinema of France as European Cinema, or the Cinema of South Korea as Asian Cinema. They need to learn more about African Cinema before they can separate the Cinema of, say, Uganda or Nigeria, from African Cinema.

Splitting hairs over definitions is all well and good amongst a select few. But African Cinema needs to break out for these important intellectual debates to really take flight, and it is films like Who Killed Captain Alex? that will compel people to learn more, to incite change, and crucially give the entire heritage of African Cinema back to Africans in a meaningful and widespread way. Americans know their Cinema, as do British people, Chinese, Australian, French… but do Africans? We need more African filmmakers and more African academics, growing up with better resources and a more varied cinematic canon to draw upon.

By generating more interest both in and out of the continent, more than a handful of academics will engage in a discourse that moves the conversation further away from tradition Western frames of reference, and allows the art, technique and politics of African Cinema to be defined on African terms. Who Killed Captain Alex? has ushered in a more global, varied African Cinema that is advancing further towards the fourth phase- and that is why it is the most important African film of the 21st Century.

Who Killed Captain Alex?–Uganda. Dialog in English and Luganda. Directed by Nabwana I.G.G. Starring Kakule William.