This is the first in a series of interviews with key participants in African cinema that I hope will provide more insight into the local history of African moviemaking than what has been provided repeatedly in scholarly articles and books. By talking with projectionists, actors, private movie theater managers, and moviegoers, I hope to unearth the nuance and texture that are missing from the official history to help increase our understanding of African cinema, particularly the cinema of Burkina Faso. This first interview looks at the physical condition of movie theaters and how it affects the moviegoing experience.

The overall condition of movie theaters in Burkina Faso is mixed, and theaters are unevenly distributed among the two major cities—the capital, Ouagadougou, and the second-largest city, Bobo-Dioulasso—and the regional provinces. Ouagadougou has three main theaters in operation, Ciné Neerwaya, Ciné Burkina, and Canal Olympia Yennenga, which are in relatively good condition because of the privatization of theaters. However, privatization has also made the government less willing to help maintain the facilities.

Despite its size, Bobo-Dioulasso has only one theater, Ciné Guimbi, which is currently under renovation thanks to the sustained efforts of the Association de Soutien au Cinéma au Burkina Faso. These are grassroots efforts aimed at the cultural revival of Bobo-Dioulasso, which is often regarded as the economic and cultural capital of Burkina Faso. The director Berni Goldblat (Wallay, 2017) and others are at the forefront of this battle to renovate Ciné Guimbi.

In contrast, small neighborhood theaters in Ouagadougou, such as those in Tampouy and Wemtenga, are barely functioning because of the structures’ physical conditions. No functioning restrooms, broken concrete seats, rusty metal benches, and no roofs make moviegoing a bad experience, particularly during the rainy season. Repairs are long overdue, as are technological upgrades to improve projection equipment.

Theaters in the provinces are mostly closed, and the few still in operation face an uphill battle to attract moviegoers because of the need for structural and technological upgrades.

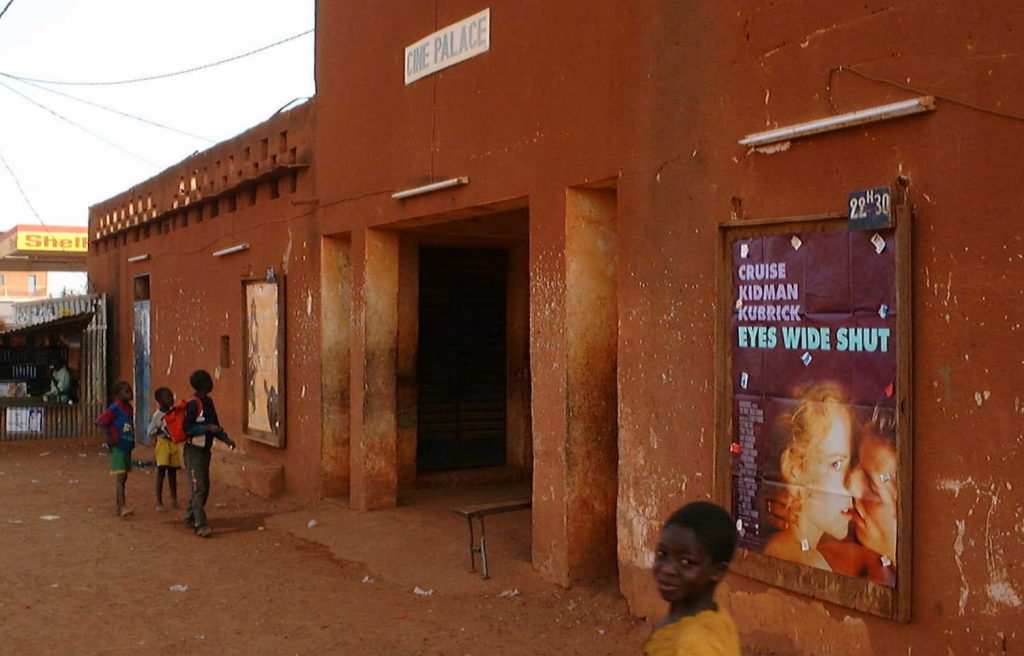

The city of Ouahigouya is a perfect illustration of the dire situation of uneven movie theater distribution in Burkina Faso. Ouahigouya is a city of about 100,000 in the northern region, and the third-largest city in the country. Ouahigouya also is the hometown of the director Idrissa Ouédraogo and where he made his critically acclaimed films Yaaba (1989) and Tilaï (1990). Yet, the city only ever had two movie theaters, Ciné Palace and Ciné Yadega. Ciné Yadega, which opened in the late 1980s, is now closed, and only Ciné Palace is still in operation – for now, at least.

Amid this gloomy picture, there is an urgency, and a responsibility, to preserve the local histories of moviegoing practices in these places that are far from the national and international cinema spotlights. On August 6, 2018, I interviewed Boureima Ouédraogo, the projectionist at Ciné Palace for the past 52 years.

• • •

Please tell me about the history of Ciné Palace and how you got started there.

I came to movies through my uncle, who would regularly take me to see films. My uncle’s friend, Yacouba Kaboré, then manager of the theater, offered me the opportunity to work as a volunteer at the age of 15. So I dropped out of school to pursue my passion. At the time, we used 16mm projection equipment, which ran on coal. We only showed black and white films because there were no color movies yet.

Ciné Palace was created 90 years ago by the French colonial administrator Valentaire. He sold the theater to Gerard Kango Ouédraogo, a politician and native of Ouahigouya. In 1974, the Frenchman Henry Bouillet leased the theater from Gerard Kango Ouédraogo until 1977, when the Beninese Calixte Moesse took over as manager under Société Nationale Voltaïque de Cinéma (SONAVOCI). The latter was replaced by Société Nationale de Distribution et D’exploitation Cinématographique du Burkina (SONACIB) in the early 1980s and privatized all the movie theaters in Burkina Faso. SONACIB has been closed for a little more than 10 years now.

Tell us how local moviegoers’ habits and their favorite film genres have evolved over the years.

Nowadays, people have different reasons for not coming to movie theaters. But when Ciné Palace was doing well, we were making on average 5 to 6 million CFA Francs ($10,000 to $12,000) monthly from 1974 to 1977 and onwards. The ticket prices were 50 Francs, 150 Francs, and 200 Francs. When I first joined the projection team, we were screening predominantly detective, Hindu (Bollywood), and action films. But westerns are still moviegoers’ favorites from the imported films.

How do you explain why people are not attending movies en masse?

Back then [the 1970s], people came to the movies in droves because there were no other viable options for entertainment, and theaters were the only places people could see movies. But today, people can get entertainment on TV, computers, even cellphones. And they can watch as many films as they want. Technological development killed the movie theaters in Burkina Faso. It is [also] the government.

How?

Take, for example, FESPACO screenings – [they] take place only in Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso, leaving aside the regional provinces. Cinema is not about bureaucrats at FESPACO or in the public administration, but rather about those who make movies and the technicians who project them. Not even once have the country’s decision-makers asked technicians for their input on the state or future of our national cinema.

What future do you see for Ciné Palace?

Ciné Palace needs major improvements to the physical structure by covering it with a roof, redesigning the interior, and installing air conditioning and more comfortable chairs. People of Ouahigouya love going to the movies, but they also like to enjoy some comfort while there. We have stopped importing foreign films for several years now, so we mostly show Burkinabe and African movies that the public like so much. We will continue to show more African productions.

Conclusion

I would like to quote from a piece I wrote earlier on Burkinabe cinema:

“By the early 1980s, the nationalization of film distribution had failed for various reasons. However, a local businessman, Martial Ouédraogo, built and equipped a film studio, CINAFRIC, in Ouagadougou (Kossodo district) to produce and distribute films. CINAFRIC was only able to help produce Paweogo (Emigrant; Kollo Daniel Sanou, 1982) before closing because of a lack of enough productions to recoup the initial investment of more than $2 million. The economic crisis of the 1990s led to the closure of movie theaters, worsening the Burkinabe film industry […] I consider the early 1980s to the 1990s to be the golden decade of Burkinabe cinema. Today, the film industry in Burkina Faso is under reconstruction by the transition of one generation to another, the gradual shift from celluloid to video/digital technologies and formats, and structural reforms led by the government.”

The Burkinabe Fonds de Development Culturel et Touristique (FDCT), established in 2017, was designed to help develop viable national cultural industries, including cinema. However, the FDCT’s budget is limited. Other programs and initiatives have to be developed to help meet the funding needs of the national film sector.

What is at stake beyond the particular case of Burkina Faso is rethinking how francophone African auteur cinema has always operated: reliance on grants as the main funding sources and establishing or reopening theaters in countries where more movie theaters are closed than open. What is the best economic model for African cinema? How should directors establish cinema as a business within national economies? How can public authorities better appropriate funds for cinema? The answers to these questions might provide the start to rethinking this process.

This article was originally published by the author in an altered format for African Journal Online.