By Pier Paolo Frassinelli, University of Johannesburg

Netflix went live in South Africa on 6 January 2016. The arrival of the subscription-based content streaming service was a game changer for the country’s film and television industry, as it had been for other countries.

At about the same time – in 2015 and 2016 – there was another turning point for South Africa’s film industry: the arrival of a new, commercially successful genre, the Black romantic comedy.

For the first time, the country’s Black filmmakers were able to make an impact at the box office – and go on to license their films to streaming platforms.

In South Africa, Netflix signaled the turn to streaming for watching films and television series. Despite a recent slowing of subscriber growth, Netflix has over 200 million paid subscribers worldwide. These numbers – and the way streaming services are reshaping content production, distribution and consumption – represent the most radical change in the film industry in recent years.

On the African continent, this expansion has had to face the challenges of lack of affordability, uneven connectivity and the cost of data. These keep Netflix beyond the reach of the majority of the population. According to data, in 2020 Netflix still had only 1.4 million subscribers across the continent. Still, in a growing number of African countries, content acquisition and production for online streaming is a fast growing industry.

And it’s not just about Netflix. South Africa-based Multichoice – owner of digital satellite television service DStv and online subscription video on demand service Showmax – has put up an effective fight for this market. Before the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, Multichoice was planning to produce 52 local movies and 29 dramas in 2020.

The company claimed that DStv and Showmax doubled South African users between 2018 and 2019 and are now locally bigger than Netflix – though it did not disclose the exact numbers.

The African romcom seems a perfect fit for the streaming market. Versions of it are still being produced and made accessible via streaming platforms today. South African romcoms Mrs Right Guy (2016), Catching Feelings (2017) and Seriously Single (2020) are currently available on Netflix. They rub shoulders with a selection of Nollywood takes on the genre, including hits like The Wedding Party (2016).

My recent article on this genre explores what some of these popular films reveal about urban middle and upper-class lifestyles and aspirations. It also considers how they reimagine Johannesburg, the city where most Black South African romcoms are set.

The romcom revolution

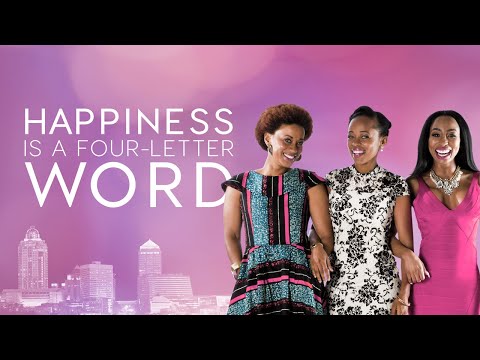

In 2016, the highest grossing local film was Jaco Smit’s Afrikaans-language romantic drama, Vir Altyd (Forever), which made over R15 million (over a million USD) at local theatres. It was followed by Thabang Moleya’s Johannesburg northern suburbs’ bling-saturated romcom Happiness Is a Four-Letter Word. This made an impressive R13.2 million in a box office previously dominated by Afrikaans films and Leon Schuster’s slapstick comedies. In fourth place was Adze Ugah’s Mrs Right Guy, which took in over R4 million by rehearsing one of the genre’s standard plots.

The year before, Akin Omotoso had directed Tell Me Sweet Something, a romantic comedy set in Johannesburg’s downtown hipster hangout Maboneng. It was one of the few Black South African films since 1994 to gross almost R3 million. South African audiences, commentators concluded, had had enough of highbrow, socially engaged films and were turning to genre flicks. In the words of journalist Lindiwe Sithole, “It seems that South Africans are leaning towards the lighter offerings.”

To understand their appeal, it is worth asking what these films say about the time and place where they are set.

The end of the rainbow

South Africa’s Black romcoms break with the tales of racial reconciliation and the rainbow intimacies of a prior generation of English-language romantic comedies. Think of White Wedding (2009), where Elvis and Ayanda’s interracial wedding in Gugulethu is joined by right wing Afrikaners ready to embrace racial diversity. Or I Now Pronounce You Black and White (2010), where a groom and bride transcend the conflict between their Jewish and Zulu parents – or Fanie Fourie’s Lobola (2013) where a couple must also overcome their families’ cultural differences.

By contrast, Tell Me Sweet Something, Mrs Right Guy and Happiness Is a Four-Letter Word are conspicuously “Black” films. In contrast to the previous generation of English-language romcoms, they all have Black directors (a sign that the South African film industry is slowly transforming).

Set in Johannesburg’s middle and upper-class cityscapes, they portray mostly young, hip, affluent, good-looking, heterosexual Black characters falling in love with each other – with the occasional split and disappointment to add spice to the quest for happiness, real passion and true love.

Joburg as glamorous global city

The emergence and mainstreaming of the Black South African romcom is also part of a broader trend in the cinema of the global south, where the appropriation of western commercial genres is accompanied by images of the “global city”.

Tell Me Sweet Something, Mrs Right Guy and Happiness Is a Four-Letter Word reimagine Johannesburg by aligning it with an imagery of global urbanism that is associated with visual and narrative repertoires of contemporary African cinemas, such as New Nollywood comedies in Nigeria. This challenges discourses and stereotypes of “African backwardness” and is often captured in aerial or high angle shots of skylines made up of tall buildings, or through images of glossy, gentrified and glitzy urban landscapes.

But there is more to this, I argue. By representing a globalized version of Johannesburg, these films are throwing up their own contradictions. They cash in on the aesthetic of an African global city even as they unavoidably continue to remind us of the city’s social conflicts and socioeconomic inequalities. They do this in their storylines as well as their images.

All three films repeatedly reference a more authentic version of the city as an object of love and desire. This is evoked not only through the high angle shots of some of Johannesburg’s most densely populated urban areas, but also through images of some of its newly gentrified downtown neighborhoods and via their characters’ desire for loving, inhabiting and being part of “the city”.

These films are not simply a celebration of consumerist lifestyles. They also represent the tensions and dislocations that accompany the Black majority’s occupation of affluent urban spaces and its embrace of the consumptive practices from which it had so long been excluded. It is no surprise they have turned out to be popular, boosted by the demand for streamed content.

Pier Paolo Frassinelli, Professor, Communication and Media Studies, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()