Cairo Station, released in 1958, was the eleventh film of Egyptian cinema titan Youssef Chahine. It was also his most controversial feature up until that point in his career. This suspenseful psychological thriller is an unabated deep-dive into the budding neuroses of a handicapped young man scrounging for a living in a Cairo train station, and the fatal repercussions of his perverse unrequited romantic desires.

Youssef Chahine (1926-2008) was by far the most prolific of all the early masters of cinema on the African continent. His first film, Nile Boy, set him on the path to a successful career in the then-dominant Egyptian film industry, and garnered attention outside Egypt when it screened at 1951’s Cannes Film Festival.

Cairo Station, also titled The Iron Gate or Bab El Hadid, is arguably the crown jewel of Chahine’s expansive oeuvre. However, the film was much-maligned upon its release. Chahine, who became a favourite of Egyptian film-goers for his vibrant melodramas, flipped the script on them in Cairo Station by exploring the dark underbelly of life in Cairo. Cairo Station is widely considered Chahine’s first stylistically distinct film. His filmmaking sensibilities in the late fifties grew to accommodate influences from other filmmakers, genres, and creative and social movements on the global scene. Many of Chahine’s fans found Cairo Station to be a jarring departure from their expectations of his work

Explosion of Life and Lust

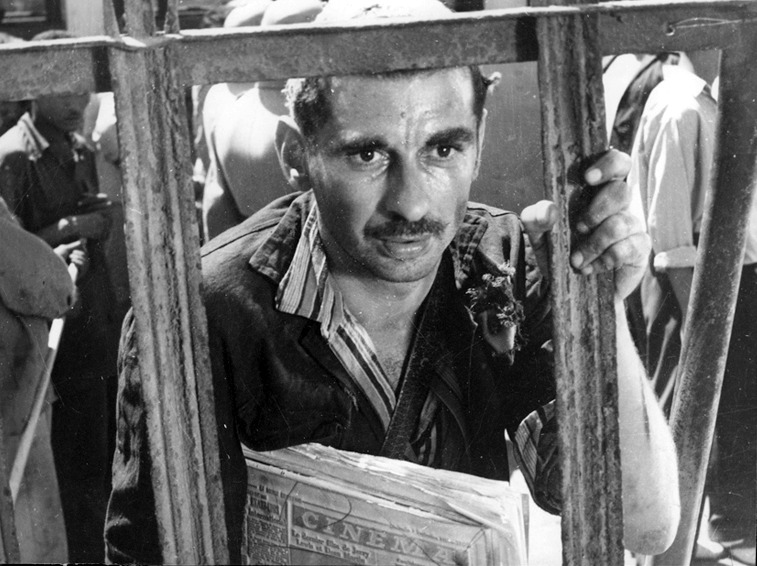

The film opens on a montage showing the explosion of life that is post-Revolution Cairo’s train station. A voice of God narration by Madbouli, a newspaper vendor at the train station, underlines the sequence. Besides romanticizing the station, he reminisces on how he came to be the guardian of the film’s antihero Qinawi, a handicapped, shy, and lonely young man who works menial jobs at the station. The final shots of the opening sequence show Madbouli visiting Qinawi’s shack by the rails, and standing in utter shock at the dozens of cutouts of nude models pinned on the walls.

Youssef Chahine himself plays Qinawi. He cuts an uneasy introverted figure; his twitchy, evasive demeanor signals an inherent self-loathing and lack of self-esteem. His sly leering at unsuspecting individuals highlights a dysfunctional view of social interaction and etiquette, especially with women. The two other key characters in this narrative are Hanouma and Abu-Serih. Hanouma is a vivacious, free-spirited, and witty soft drink vendor at Cairo Station. She is also very attractive. Hanouma is to be married to the physically imposing and charismatic Abu-Serih, a station porter who leads the charge for creating a workers’ union, to improve the wellbeing of his colleagues.

Judging by their initial interactions, Qinawi and Hanouma are friends. Early in the film, Hanouma leaves her soft drink bucket with Qinawi as she tries to evade station authorities. However, when Qinawi returns the bucket to Hanouma, he hides out and ogles her as she changes out of wet clothes. Hanouma discovers him doing so. She throws him out, setting a pack of stone-wielding children on him as well. He evades the children and returns to his shed, where he dumps water on one of his lewd pictures to remind himself of Hanouma.

From this point forward, Cairo Station documents Qinawi’s increasingly troublesome pursuit of Hanouma, alongside other subplots like Abu Serih and Hanouma’s impending marriage, Abu Serih’s unionizing activities, and seemingly unrelated events around another young couple that Qinawi eavesdrops on.

An Early Take On Toxic Masculinity?

One of the most interesting aspects of Cairo Station is its unflinching examination of how perpetual sexual repression has an adverse effect on antihero Qinawi’s mental health. Many African societies persistently neglect mental health in their social discourse, even more so for men who must adhere to rather dated standards for masculinity. While Qinawi’s transgressions in the film are his own, and cannot entirely be attributed to his mental health, it is startling to see how much of an effort Chahine put into giving context to the main character’s socially unacceptable behaviour.

Cairo Station thrusts the emotional deprivation that Qinawi experiences front and center as a key catalyst for his actions. He appears to have few real relations outside of Madbouli and Hanouma. His obsession with the nude model cutouts, and his need to furtively gawk at the young couple in the station, serve as symptoms for his loneliness.

One could compare Qinawi to the 21st century internet incel. The term is a contraction of “involuntarily celibate,” and refers to anyone who subscribes to the ideas of a fringe online subculture of heterosexual men who identify with their inability to find a female sexual partner. Incels are also known for their denigration of female rights and sexual liberties, as well as justifying rape and other forms of violence against women. In more developed countries such as the US, incel forums have evolved into a hotbed for some young men who go on to carry out racially or religiously motivated mass shootings and other acts of terror.

Disturbing as the existence of these vile, self-loathing, misogynistic characters may be in the virtual world, they also hide in plain sight in the real world. Entitlement to sex and male expectations of female submissiveness are still the norm in many conservative patriarchal societies in less developed parts of the world. In many African societies that still embrace hegemonic masculinity, crimes against women such as domestic battery, marital rape, and assault are justified by shifting blame to the woman—be it for her conduct or way of dress. Could it be that Youssef Chahine had his finger on the pulse of the feminist undercurrents of the time, and sought to investigate the evolving nature of gender relations in the developing world? Did he seek to demystify gender-based crimes by highlighting the connection between violent acts against women and the subtle nuances of the male psyche?

Subversive Styles

As previously mentioned, the production of Cairo Station coincided with Youssef Chahine’s creative rebirth as a visual artist. His earlier films had been in the mold of conventional melodramas and comedies that were staples of Egypt’s early film industry. The period spanning the late 1950’s and early 1960’s is widely considered a watershed moment in cinema for how the masterworks of various iconoclasts, national cinemas, and artistic movements (ex. Neorealism, auteur theory) entered mainstream film discourse. It would not be far-fetched if Chahine’s shift to a more subversive filmmaking style was a result of these influences of the time. In Cairo Station, he very cleverly distills his newfound cinematic lens into the film’s mise-en-scene.

For instance, the film makes heavy use of high-contrast lighting to express Qinawi’s shifting mental states. The lighting in the film gets progressively darker and more uneven the further we descend into the impulsivity of Qinawi’s actions. This use of lighting to express the psychology of flawed characters was commonplace in the film noir genre, but noir films were long out of fashion by the time Cairo Station was made.

Considering the drastic differences of Cairo Station’s visual semiotics from Chahine’s previous works’, it seems like his use of Chiaroscuro was a stylistic choice, as opposed to an attempt to follow prevalent trends. The cinematography of Cairo Station is also much more fluid than that of other late 1950’s Egyptian films. In many of the film’s key scenes, the camera is handheld and mobile. Furthermore, the film uses many close-ups and point-of-view shots. Seeing as this is a psychological thriller, these techniques place the audience in Qinawi’s head, allowing them to receive vital narrative information from his point of view.

Due to this iconoclasm, Cairo Station provoked outrage among Egyptian audiences upon its 1958 release, and upset some foreign critics who desired a more trend-respecting piece. Nevertheless, the film was reborn after a new generation of international film lovers discovered it in the 1970’s. Youssef Chahine directed more than thirty films after Cairo Station, but this prescient 1958 classic remains his most widely seen and revered project.

• • •

Watch Cairo Station in its entirety via YouTube