Known for the gentle poetry of his domestic dramas and the consistency of his filmmaking style, Yasujirō Ozu is one of the most acclaimed Japanese directors of all time. Having directed over fifty films throughout his four-decade long career, Ozu remained remarkably consistent in both themes and technique: his films are often quiet domestic dramas, examining the complex dynamics of Japanese middle class families through a strict aesthetic formalism.

However, a rarely discussed aspect of Ozu’s post-war films is how many of them gently push against traditional family structures and Japanese economic norms. Building on our first Ozu retrospective about why his films still resonate deeply in our era of content oversaturation, this retrospective will explore how he is a subtly transgressive filmmaker.

Gently Transgressive

When speaking about “transgressive filmmakers”, Yasujirō Ozu may not quickly come to mind. Instead, we may think of directors like John Waters, Takashi Miike, or Paul Verhoeven — filmmakers who make edgy, provocative films with graphic violence, profanity, or sexual content to shock and entertain the viewer. Ozu’s quiet domestic dramas do not initially seem to fit, with their carefully composed frames, warm humour, and subtle themes.

However, many of his films question norms in Japanese society, such as traditional conceptions of marriage, family, and romantic relationships.

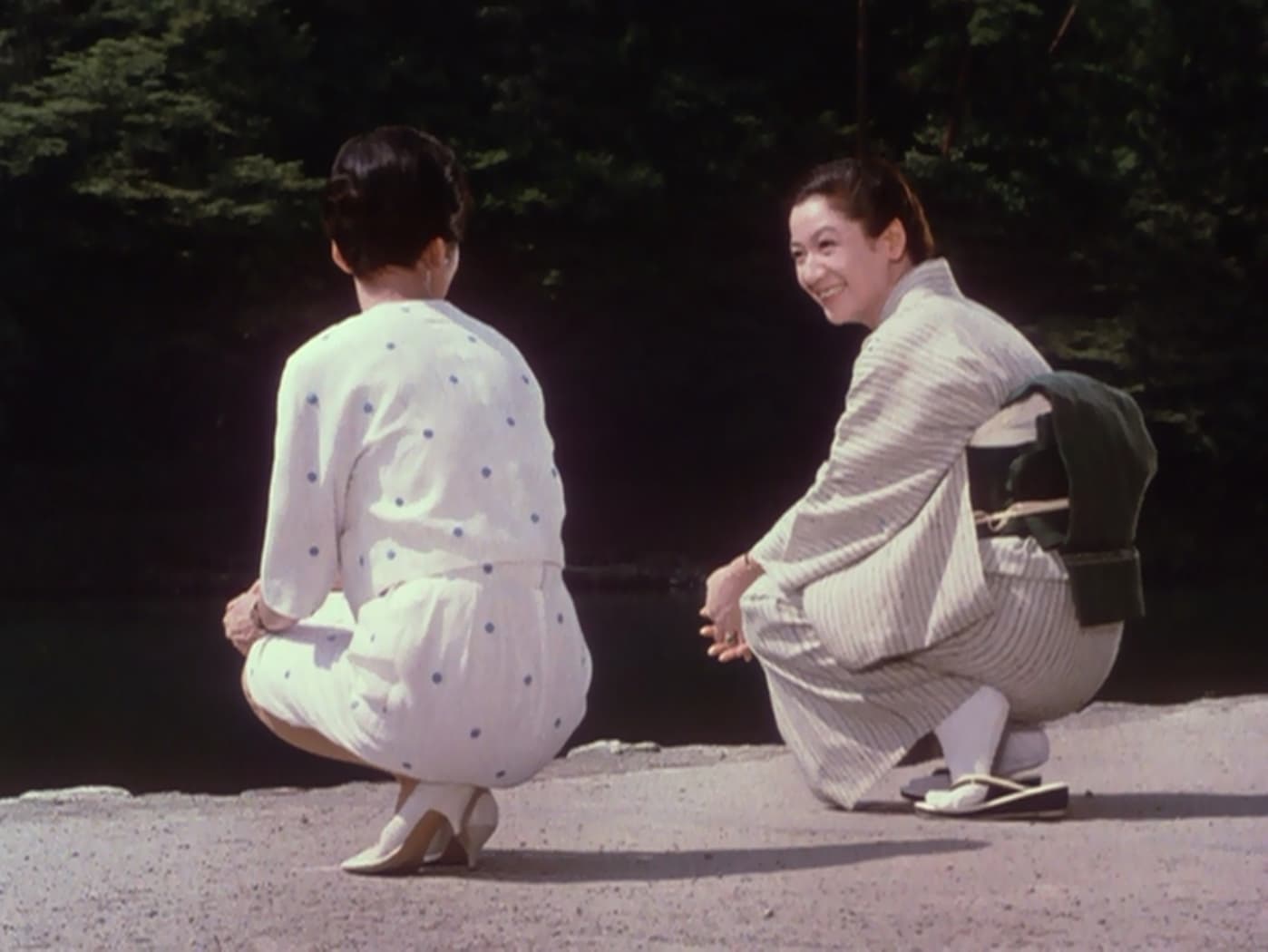

The End of Summer features a widowed daughter-in-law named Akiko (played by Setsuko Hara, one of Ozu’s favourite actors). Despite the social pressures, Akiko refuses to marry, choosing to remain alone. The recurring motif of the daughter who is reluctant to marry is repeatedly explored in Ozu’s work: it is the primary plot driver in films like Late Spring, Early Summer, Late Autumn, and An Autumn Afternoon.

Ozu’s fascination with this topic may stem from his own experiences with Japanese societal pressures. Ozu himself never married, instead living with his mother for all of his life. While he never explicitly came out as gay or queer, he was expelled from boarding school as a teenager for writing a love letter to another male student and appears to have never had an active romantic relationship with a woman. While we can only speculate about the truth of his sexuality, I believe that his experiences in boarding school, combined with the experience of living with his mother as an unmarried man for all of his adult life, would have offered him profound insight and empathy into the pressures of societal expectations regarding marriage and relationships in post-war Japan.

In the five films mentioned above, Ozu explores the impact of these pressures and the expectations placed on unmarried Japanese women, whether the women succumb to these pressures or, as is the case in The End of Summer, they choose to reject these social norms.

Ozu further explores the idea of forbidden love in many of his other post-war films. In Floating Weeds, a remake of his earlier silent film of the same name, we see a young man fall for a sexually promiscuous woman who is beneath his status. Films like Early Spring and The Munekata Sisters explore romantic longing and loneliness between people in and outside of the norms of marriage, while in Equinox Flower, the daughter explicitly fights against the traditional Japanese norms around marriages, rejecting her father’s arranged marriages and instead choosing to marry for love.

Gently Anti-Capitalist

In addition to pushing against Japanese norms regarding love and marriages, Ozu’s post-war films also critique the structures of Japanese capitalism, which continued to boom in Japan following World War II.

Early Spring, Ozu’s longest surviving film, examines the monotony of the salaryman Soji Sugiyama (played by Ryō Ikebe), or, as Ozu puts it, “the pathos of the white-collar life.” This theme is repeated in several of his other films, such as Good Morning and Equinox Flower, but never as centrally as in Early Spring. The inhumane drudgery of Sugiyama’s life at the fire brick manufacturing company begins to drive his existential crisis, his depression, and ultimately his extramarital affair.

Another explicit condemnation of the burgeoning capitalism in Japan occurs in The End of Summer. The protagonist Manbei Kohayagawa (played by Nakamura Ganjirō II) is the head of a small sake brewery, struggling to survive amidst pressures from larger firms and business rivals. As they discuss the possibility of succumbing to a merger, Kohayagawa states “you cannot win against big capital”. It is one of the few moments in an Ozu film where characters explicitly articulate the pressure and inequalities of a capitalist system.

All of these films feature examples of Ozu critiquing Japan’s post-war economic model, which prioritized manufacturing, high growth rates of production, and the continued dominance of the salaryman.

Cozy Critical Cinema

While Ozu’s films may be gently transgressive, they still remain perfectly cozy watches for the winter months. If you are in the mood for a peaceful domestic drama that pushes against societal expectations, settle in with a film by this great Japanese auteur. I encourage you to seek out Ozu’s films wherever they are showing. For example, The Cinematheque, an arthouse theater in Vancouver, Canada, recently screened ten post-war Ozu films as part of their Ozu 121 series. As cultural and educational institutions dedicated to showcasing essential cinema, independent theatres like The Cinematheque play a vital role in keeping Ozu’s films alive, exposing a new generation of viewers to the work of a true master.