In 1985, North Korea made Pulgasari, a Kim Jong-il approved Godzilla ripoff. As the Korean peninsula enters a new period of rapprochement, the messages within Pulgasari, and the story behind its making, have renewed relevance. Revisiting the film provides an amusing way of better understanding North Korea—and its motivations for diplomacy.

North Korea makes far more movies than most people expect, thanks in part to former leader Kim Jong-il’s infamous penchant for cinema. In both plot and execution, Pulgasari feels very different from most other North Korean films.

Set during Korea’s feudal Goryeo period, Pulgasari tells the story of a group of peasants who rise up against an oppressive king. While this might sound subtly communist, Pulgasari is light on overt political messages. Compared with other North Korean classics like The Flower Girl or Order Number 27, the film doesn’t follow traditional “revolutionary opera” tropes or include odes to Dear Leader.

Instead, the film centers around a young woman named Ami, the daughter of a village blacksmith imprisoned for opposing the evil king. Right before the blacksmith dies in prison, he fashions a reptilian figurine out of rice and wills it to avenge his death.

Meet Pulgasari: North Korea’s Godzilla. The blacksmith’s incantation comes true—with an accidental pinprick of Ami’s blood, the figurine comes to life as a monster named Pulgasari. Initially tiny (Ami even calls him “cute”), Pulgasari starts eating iron, and resultantly grows to a massive size. With impenetrable scales and super strength, Pulgasari fulfills the dead blacksmith’s wish by helping Ami and her fellow villagers defeat the evil king.

However, even after victory, Pulgasari still hungers for iron. Realizing that keeping Pulgasari will require her village to feed him their farm tools and cookware (thus condemning them to starvation), Ami sacrifices herself to quell Pulgasari’s appetite once and for all, tricking the monster into swallowing her whole and lifting her father’s incantation.

Past critics have interpreted Pulgasari as a metaphor for unchecked capitalism. In light of ongoing rapprochement on the Korean peninsula, we might be able to see the film through a new lens—as an unintentional parable about peace.

Pulgasari‘s plot conveniently dovetails with Kim Jong-un’s possible motivation for peace talks. North Korea (the villagers) has developed nuclear weapons (Pulgasari), which allows it to stand up the US (the evil king). However, these weapons bring economic and social costs thanks to sanctions, just as Pulgasari’s appetite for iron threatens all the villagers’ tools. Thus, putting denuclearization on the table (i.e. getting rid of Pulgasari) gives Kim Jong-un more breathing room to revive North Korea’s economy.

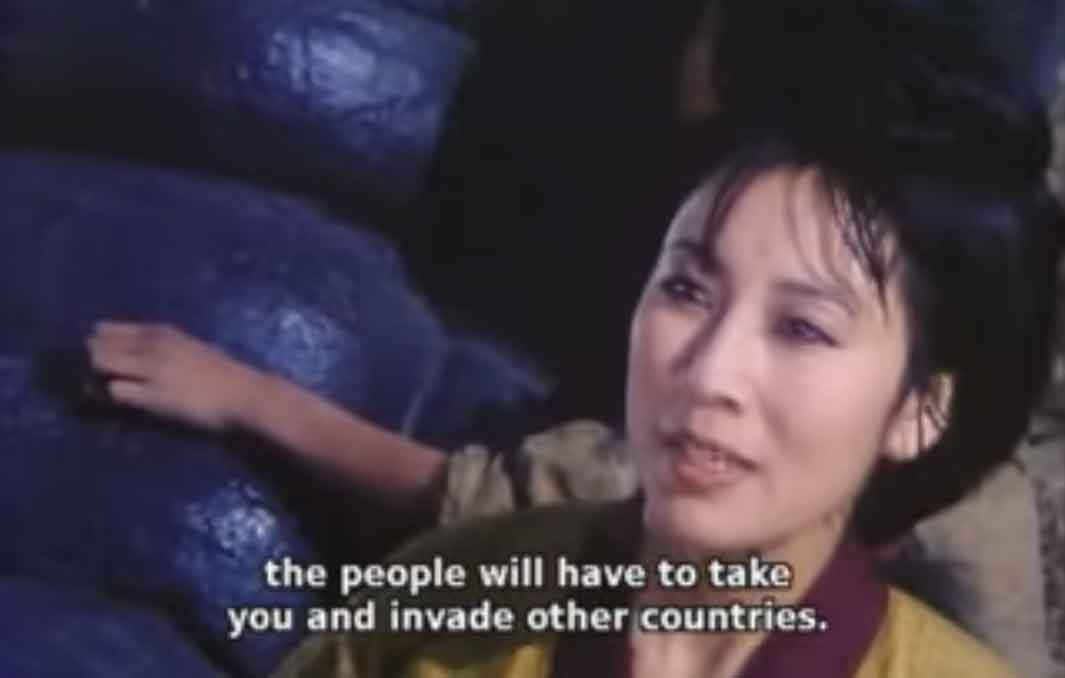

You could even see Pulgasari as a broader metaphor on nuclear hegemony. Towards the end of the film , Ami mentions how Pulgasari’s insatiable thirst for iron will eventually require the villagers to invade foreign countries. Perhaps this is another subtle jab at North Korea’s preferred punching bag: the nuclear-armed American imperialists.

In denuclearization negotiations, North Korea will likely look for opportunities to place itself on moral high ground, as Ami does when she realizes Pulgasari must go. The key here is that Ami only gets rid of Pulgasari after the evil King is gone—mirroring North Korea’s desire for ironclad security guarantees like removing US troops and nuclear capabilities from the Korean peninsula.

While Pulgasari‘s plot has become a fun way to explain the latest rounds of North Korean diplomacy, that likely wasn’t Kim Jong-il’s intention in the early 1980s, when he first commissioned the film. North Korea’s nuclear program was still in its infancy back then, and the country’s economy was in a less precarious state. However, if we look at the behind-the-scenes story of Pulgasari‘s making during that time, we can see further hints of North Korea’s negotiating mindset.

One big reason why Pulgasari feels different from other North Korean movies is because many non-North Koreans helped make it. Notably, the film’s director Shin Sang-ok was South Korean. In a bizarre incident recently popularized in the novel A Kim Jong-il Production, Kim Jong-il kidnapped Shin and his wife to help rejuvenate North Korea’s movie industry.

Similarly, the film involved Japanese personnel, despite North Korea’s intense dislike for Japan due to brutal colonial treatment. Pulgasari was actually played (in a rubber suit) by Kenpachiro Satsuma, the same actor who played Godzilla in numerous Japanese films of the franchise. While not kidnapped, North Korea initially duped Satsuma and his fellow Japanese crew into believing they were helping a Chinese production.

Why would North Korea go to such lengths to kidnap and trick people from sworn enemy nations? Likely for the same reason that Kim Jong-un wants to meet personally with Donald Trump: a desire for legitimacy.

In the early 1980s, Kim Jong-il wanted the world to take North Korean cinema seriously. Kim knew that North Korea couldn’t do it alone, and thus kidnapped Shin Sang-ok. Pulgasari became Kim’s pet project. After seeing Godzilla‘s success, Kim saw the monster movie genre as North Korea’s best chance at impressing international audiences. This led him to green-light collaboration with Japan’s Toho films (which made the original Godzilla); he also dispatched thousands of soldiers to play extras in Pulgasari’s battle scenes.

All this goes to show a ruthless determination to assert North Korea’s legitimacy on the world stage—a sentiment that’s likely helped keep talks between the US and North Korea alive despite Trump’s vacillations.

Of course, that single-minded ruthlessness cuts both ways, and could very well doom North Korea’s further attempts at international recognition. Director Shin Sang-ok exploited Kim Jong-un’s international cinema aspirations to escape while on a trip to Vienna, ostensibly for talks about distributing Pulgasari. Thanks to this, Pulgasari never achieved the international renown Kim Jong-il craved. After Shin’s escape, Kim purged the film.

Yet, thanks to the shifting tides of statecraft, Pulgasari somehow survived. In July 1998, around the launch of South Korea’s conciliatory “Sunshine Policy”, Kim Jong-il authorized a Japanese release for Pulgasari. This helped the film become a cult hit outside North Korea, where it continues to live on through YouTube and indie theater screenings. Two decades later, on the cusp of another potential reconciliation with North Korea, Pulgasari might be due for another resurrection.

• • •

Pulgasari is watchable in its entirety through YouTube…