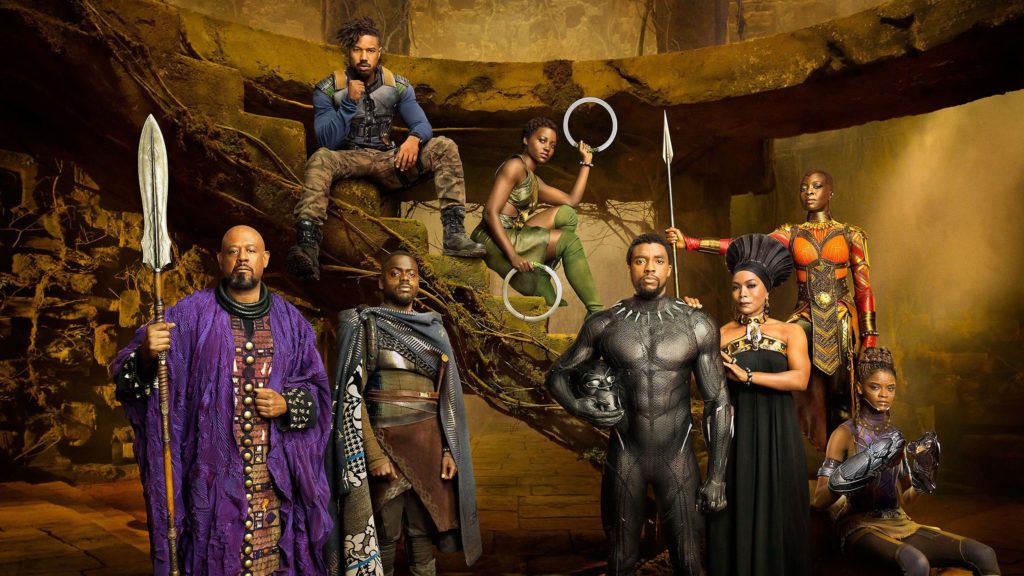

The records that Black Panther has been breaking, and the conversation it has been inciting, show that the film has not just been successful—it has become a worldwide phenomenon. In Hollywood, at least, the last few years have done nothing but prove that audiences are ravenous for more diverse films that better represent them.

Not only that: audiences are calling out for more diverse casts and crews in an increasingly loud volume, bolstered by social media, and the film industry is starting to respond. It’s all a step in the right direction, with films like 12 Years A Slave, Moonlight and Get Out leading the conversation both at the box office and on the awards circuit. But Black Panther has come along and it’s already one of the biggest films in US box office history in less than a month. This isn’t just an anomaly; it’s a milestone regardless of how good the film actually is.

But what exactly does Black Panther‘s impact mean for the Cinema of the continent it depicts? It could be a huge step forward for African Cinema, but only if African filmmakers utilize the opportunity presented by Disney, Marvel, and Ryan Coogler. Black Panther‘s biggest takeaway is that African filmmakers can tell authentic stories their own way and audiences will turn out.

However, to reach even a fraction of the audience that Black Panther has enjoyed, which in turn can lead to better support by distributors worldwide and encourage development of African Cinema, there has to be some compromise in the same way that any commercial film must often suffer to appease those holding the purse strings.

Compared to what has come before, Black Panther offers a very forward-thinking representation of Africa and its diaspora. This presentation paid off partially because the film had social momentum behind it, and also because it is part of a globally recognizable brand. But it is an American film first and foremost. Since America is still the dominant force in terms of cinematic output, the fact they even made Black Panther is a step in the right direction.

Audiences Are Open To Being Challenged

Black Panther has to be considered on two fields—what it is like as a piece of art, and what it stands for as a cultural phenomenon. If criticism of the film does not separate these two factors, it does a disservice to both.

It is yet another installment in a franchise of comic book superheroes; crowd-pleasing blockbusters that must appeal to four quadrants, and is therefore likely to be watered down in order to have the widest possible appeal and make as much money as possible. This installment just so happens to be based on characters who are mostly African, and primarily takes place in a fictional African nation. It was never going to be a complex dissection of the African experience.

Whilst there are plenty of things to enjoy about the film, and director Ryan Coogler clearly instills plenty of his own personality into the movie (from the scenes set in his hometown of Oakland, California to his lifelong love of the lead character), I would argue that Black Panther is Coogler’s weakest film. This seems to be more down to the restrictions of blockbuster filmmaking, and the staggering ambition of the film eclipsing what should have been story with a leaner pace and a more focused structure, than the talent of its director.

However: it is still miles better than most of today’s Hollywood fare. It tackles big issues and bold themes, yet balances them out with some well-choreographed setpieces and is anchored by plenty of strong performances.

Whether the film succeeds in its social commentary is besides the point—everyone is talking about the film before they have even seen it. As such, audiences will come out of the film discussing its most prominent themes. Black Panther addresses the Atlantic slave trade, African American upbringings (through how it shapes the film’s villain), and focuses on its lead protagonist and antagonist clashing over how to deal with the outside world—T’Challa initially sees a less advanced world that cannot be trusted with what Wakanda has to offer, whereas Eric Kilmonger wants to conquer and utilize Wakanda because they have abandoned their oppressed descendants across the world. It’s not necessarily a big deal that the film focuses on these issues, but it is a huge deal that they are raised and discussed within a film that is being shown on a global scale.

Africa Can Improve Upon Black Panther‘s Efforts

Black Panther is a gateway to Africa for mainstream audiences, regardless of their heritage. Specifically, it’s a gateway to a more positive and balanced depiction of the African Continent and Diaspora, and its people. Black Panther is far from the best or most accurate depiction of Africa or Afrofuturism. It is, first and foremost, a commercial blockbuster bankrolled by an American corporation with many white executives and producers.

The film represents a cultural milestone, but so much more can be done. Director Ryan Coogler admirably presented a different vision of Africa, but African Filmmakers can improve upon this. To be fair: some already are, but their films lack wide distribution.

It’s clear that the team behind Black Panther, from Coogler and composer Ludwig Goransson to production designer Hannah Beachler and costume designer Ruth Carter, set out to create a world that felt like an Africa hardly seen on screen before.

Black Panther‘s dialect coach, Beth McGuire, utilized the casts’ diverse heritage to create an authentic set of “Wakandan” dialects based off real African languages like Xhosa. The film’s soundtrack features music from Senegalese musician Baaba Maal, much to the delight of Senegalese audiences. Coogler weaved all kinds of African influence into the DNA of his film, which is one factor that can explain the positive reception the film has received in Africa.

More informed and cineliterate critics may argue their attempt was inaccurate or inauthentic, and they may be right. But the point is that their efforts were far more ambitious and well-intentioned than anything that mainstream audiences have seen en masse before. Surely even the most hardened of cynics would argue the fictional Africa of Black Panther sets a better example than the likes of Blood Diamond or Coming to America.

Black Panther also exhibits Pan-Africanism to create its world, and is a notable addition to Afrofuturism. However, just because it presents a forward-thinking representation of Africa doesn’t mean it cannot be bettered. The film has proved worldwide audiences are open to Afrocentric films, and one would think that African Cinema would have achieved some level of this impact on a smaller scale.

But it’s hard to believe that, as things stand, we’ll see an influx of bold African movies that redefine how people view the continent getting some sort of international release on digital platforms, let alone cinemas, based on the success of Black Panther.

The unfortunate reality is that until Africa’s distribution and exhibition models improve, African filmmakers will have to do things on the terms of others in order to get their films out there. However, the likes of Black Panther and Get Out have demonstrated that stories told by African Americans will translate into massive financial success, both to wide and limited audiences. This is a step towards progress, and African Filmmakers need to look to their African American counterparts to encourage that (at least, when it comes to economics).

Encouraging Cultural Exchange

It seems like African audiences have responded well to Black Panther. According to The Los Angeles Times, Black Panther scored the largest box office debuts ever in West Africa and East Africa, generating about $400,000 and $300,000, respectively. In South Africa, Black Panther had the third-highest opening, at $1.4 million. IMAX Corp. also reports that its theaters in Kenya and Nigeria had their biggest results ever on opening weekend. Black Panther clearly means just as much to African audiences as it does to Diaspora audiences.

It is arguably more important that Black Panther was made in the West, than if it was an African production, as that proves progress is occurring within a culture where cinema is so dominant. It’s pretty pathetic that Third Cinema (a term that traditionally refers to a movement in Latin American Cinema, but has also been used by some to refer to the Cinemas of Third World countries) has had to wait for the West to catch up, but those first steps have been made, so cultural exchange going forward may be that less jarring—and crucially, it is the culture that Black Panther identifies as the backward, antagonistic force in the world that has made the first move.

In my personal experience over the last few years, trying to chart the intersection between the Cinema of the African Continent and Diaspora, I’ve spoken to both African and African American filmmakers. The issue I seem to hear a lot is that African American filmmakers who have been able to navigate the American film industry on their own terms, and been successful doing so, have had their efforts to support and offer guidance to African film industries fall on deaf ears.

This is based only on my few anecdotes, but it is surprising that whilst African American stories and filmmakers are slowly going from strength to strength over the past few decades —and serious progress has been made, even if it has been a painfully slow process —there has been no vocal support from, or notable collaboration with, African film industries.

Also, it seems highly unlikely that many African American audiences and filmmakers have ever been exposed to African Cinema. This is due to poor distribution and exhibition models within Africa, but African Filmmakers need to step up and improve efforts to expose the Diaspora to what they have to offer. I would be fascinated to know how many African films Ryan Coogler and the Black Panther creative team may have seen before or during the film’s production.

It seems like Ryan Coogler is the first African American filmmaker of note to transport his audience to Africa. I cannot think of any African films that really focus on seeing Black America through African eyes. The only significant example of an American getting involved with African Cinema that I can think of is Martin Scorsese’s attempts to restore 50 classic African Films through the World Cinema Project. I may be wrong on all counts, but the fact I have to really research for examples, as opposed to being able to recall at least one example from memory, sort of proves my point. If there is any real relationship between African and African American Cinema, it’s hard to find.

There are scarce examples of interaction between African and African American films and filmmakers, and Black Panther is likely going to be the most recent and notable example of this kind of interaction for the foreseeable future. In fact, it may be the only film that explores the relationship between Africa and African Americans in such depth. The film features an antagonist from the Diaspora who comes to Africa with the intention of utilizing the resources of an African nation for, in his mind, the betterment of the both the Diaspora and the Continent as a whole—it is surprising to see this play out in yet another installment in a Hollywood comic book franchise.

But because of just how big Black Panther has become already, it could be the bridge between the film industries of the Continent and the Diaspora. Both sides are more willing to get involved with each other—but from what I have learned, the ball is in African Cinema’s court and it’s up to the filmmakers of the Continent to make the effort to learn from their American counterparts, and encourage them to get more involved. In terms of making their films a financial success, there is much they can learn from African American Cinema.

Genre Filmmaking Could Be The Key To Crossover

The biggest problems with African Cinema are distribution and exhibition, both in and out of the Continent. Despite the record-breaking numbers for Black Panther in African theaters, the numbers reported in the entire region of West Africa came from less than 50 screens. This severely limits African Cinema more than anything else. Not even Africans are exposed to enough of their own films, let alone the rest of the world’s audiences.

The Los Angeles Times notes that there is potential for growth, but it is going to take time, regardless of whether Hollywood produces more films like Black Panther. Following China’s example, if international fare does not whet the appetites of African audiences, there should be a distribution model in place to offer them films from their own continent that can make serious profit, as the likes of Wolf Warrior 2 and The Mermaid have in their native China.

Black Panther‘s success may help the development of more theaters, since it has proved there is money to be made as Africa’s middle class as disposable income increases. Still, it’s up to African Filmmakers to fill those theaters with African content.

African Filmmakers need to produce films that will have crossover appeal, and that does not mean they have to just cater to Western audiences. More importantly, for a continent whose future seems far more entwined with China, you would think there would be serious attempts to capitalize on their economic closeness to what will soon be the world’s largest film market. But that’s another article for another time.

Filmmakers like Cedric Ido (Hasaki Ya Suda) and Michael Matthews (Five Fingers For Marseilles) have produced Westerns and Samurai films recently, but these are exceptions rather than the rule. Genre films are more likely to break through because they are removed from reality, and therefore more accessible. Most of the films to gross over a billion dollars worldwide are Science Fiction or Fantasy films.

It will be a long time before any African film has the production and marketing budgets of Black Panther, but in an age of production companies like A24 and Blumhouse, and franchises like Cloverfield, there are clever ways to reach audiences despite low budgets.

For example: it’s surprising that there is a lack of African Horror. The likes of Blumhouse have show that low-budget horrors often make a huge return on investment, and generate franchises that continue that profitability. Africa is full of rich folklore that would make for unique horror films, and this genre automatically has a receptive, rabid fanbase willing to consume any output.

There are some examples of African Sci-Fi (besides District 9), such as Kenyan Wanuri Kahui’s short film Pumzi. But pretty much every notable example of Science Fiction that features cast and crew of African or Diasporic heritage in the last 50 years, from Sun Ra’s Space is the Place to Ngozi Onwurah’s Welcome II The Terrordome, and now Black Panther, has been the product of creatives from the African Diaspora as opposed to those from the Continent.

Afrofuturism, which is so prevalent in Black Panther, originated amongst the Diaspora rather than in Africa. To sum it up in simple terms: Afrofuturism conceives a utopian future that is predominantly Black, where those from the Diaspora have total control of their own destiny; this is often infused with elements of technological advancement and Science Fiction. Afrofuturism seems to mean more to Diasporic audiences than African audiences, because it is so uniquely a Diasporic concept and aesthetic, despite heavily featuring Africa’s culture and history. There is a gap in the market to forge a truly African vision of Science Fiction, and African filmmakers could explore this within that most translatable and lucrative of genres.

Learning From Black Panther’s Success

Above all else, money talks. Whether you liked it or not, Black Panther is the biggest, most expensive Hollywood film produced for global audiences which demonstrates that diversity results in huge box office returns, because it is more representative of the audience as a whole. It also happened to present a very different portrayal of Africa to audiences who wouldn’t normally see a superhero blockbuster, but went to see Black Panther despite its genre. That’s a big group of people whose perceptions of Africa may be altered to some extent.

Most audiences have only seen Africa in films that portray the Continent as one big impoverished place rife with disease, war, and terrorism—with no consideration for the distinct cultural differences of cultures and regions. This is a woefully inaccurate and dated generalization, yet it is the most prominent representation most audiences have seen of Africa.

Black Panther is not going to improve things overnight, or be the sole film that changes everything. However, it is a pioneering film almost by accident. Simply by showing a different side to Africa, one in which an African nation is more advanced than the rest of the world by centuries, it’s been groundbreaking. This is how woeful the situation is: that it took a multi-million dollar comic book movie to offer a different perspective of Africa, one that is hyper-stylised and fantastical, that the masses would be exposed to.

Just look at the most successful foreign-language films outside of their own country of production—for example Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon; Hero; Life is Beautiful; Pan’s Labyrinth; Amelie and Cinema Paradiso. These films all transcend their own culture and language because they are either Genre films, love stories, or accessible crowdpleasers—much like Black Panther. What African Cinema lacks is a breakout hit like the aforementioned films. Only so much blame can be attributed to poor distribution models within Africa, especially in the Internet age.

No film that is not in the English language is going to been a monumental success outside of its own country, and it’s hard to believe that any African film could ever make the same numbers as Black Panther. But African films can at least achieve the same success and level of cultural awareness as films from Asia and Europe. They can be part of awards season conversation (there are some examples like Tsotsi and Inexba, but they are few and far between), and achieve cult status after their release.

The only time anyone outside of a small group of cineastes and academics will talk about African Cinema is when the odd independent arthouse film does well on the festival circuit, or something as comedic as Who Killed Captain Alex? captures the attention of the internet-savvy community and goes viral through memes and social media. Foreign-language films from Europe and Asia are consumed, praised and talked about far more often by far more people.

The situation is never going to change for African Cinema if creatives and executives on the Continent are happy to remain stagnant, producing both self-sustaining Nollywood productions and the occasional independent arthouse film that might receive some critical acclaim. There is an appetite for these sorts of films, of course, but if African Cinema doesn’t look outwards, how can it expect to draw in anyone but the most receptive?

However much we may consider the artistic merit of filmmaking, it has always been a business first and foremost. Commerce will always trump Art when it comes to filmmaking, even if that means sacrificing quality. The sooner more African Filmmakers accept that, the sooner significant change can be brought about.

Those of us who want to learn more about the Cinema of the Continent and Diaspora will make the effort to seek out the kind of African films being made now, but we are a limited number. It is the 21st Century, and yet whilst film lovers and the general population might talk about films from Europe and Asia, they seem oblivious to the output of a continent made up of 54 film industries. Once this begins to change, then African film industries can truly begin to take control of the narrative.

Someone needs to create a film that can crossover because it is accessible and transcends its culture without betraying it. You cannot engineer a film that you know will do that, but if that is the intention by African film executives, then it is more likely to pay off. Think big, and through trial and error something will hit a nerve with audiences. Small Genre films like Get Out had a widespread appeal. Who Killed Captain Alex? had a widespread appeal within a niche audience. There are plenty of ways this can work. But there has to be better distribution models in place throughout Africa, whether that can be achieved through building more movie theaters or utilizing the likes of Netflix.

If African filmmakers don’t capitalize on what has maybe been global audiences’ biggest and most positive exposure to Africa in history, then when will they? To get more people seeing a wider variety of African films, whether they are accessible to the masses or more sophisticated pieces of art for the more discerning filmgoer, there will have to be compromises at the start for international markets that are only just beginning to open their eyes to the possibilities of films set in Africa.

This may be a bitter pill to swallow for those African filmmakers want to break out into the wider world on their own terms, but it is hard to imagine a better time to introduce more people to African Cinema, and therefore get more African films seen outside of the Continent and Diaspora.